I'm not a theater-goer. Going to a play is not necessarily on the top of my list for a night out. Yet I sometimes enjoy reading plays. I realize this is like reading sheet-music and lyrics without hearing the music performed: the performance and the emotions of the performer gives meanings to the notes, to the words: the reader/listener is not experiencing the piece as it's meant to be experienced. But, then again, perhaps reading a play without knowledge of the performance, without the stigma of comparison. Just as when reading the book before the movie, we are the directors of what we read.

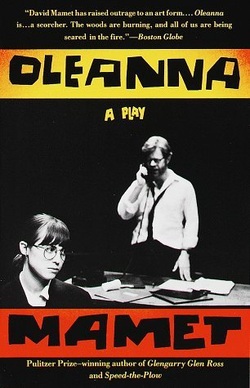

So I read Mamet's Oleanna yesterday. And, despite my preference for having an unfettered imagination when I read, without having a preconceived notion of how the characters are supposed to sound or look like, I could not help but be influenced by the cover of this edition: William H. Macy and Rebecca Pidgeon (Mamet's real-life wife). However, in this instance it did not bother me; in fact, I felt the preconceived image of these two unsympathetic characters contributed to my enjoyment. Pidgeon naturally has a stilted way of speaking, as if she's popping the bubbles of the words that have just formed, chopping them in half with her mouth, that I could hear in Carol, an at first seemingly hapless, confused student. Pidgeon's is a voice that yields itself well to self-righteous indignation and victory, which also follows the arc of her character. Macy's professor is a pedantic, harried, stammering man, the type who hides behind books when faced with a threat to his conviction of ideas, an intellectual capitulator who runs from his own ideas, only comfortable in the shadow of his self-directed disappointment. Macy could play this insecure cauldron of a person in his sleep.

These two voice types fit perfectly Mamet's equally overstepping and elliptical dialogue. There are many long pauses and an artistry to the employment of the ellipse. There are very few completed sentences or ideas by either character, which is one of the points of the play: neither character is fully listening to the other one, allowing each person's words and intentions to be fully misinterpreted and later easily exploited. As I said, neither character is sympathetic. The play is a very simple concept and idea executed to an expert level: an exploration of how seemingly innocuous statements can be used as attacks, of how words can be manipulated to fulfill one's purpose; an exploration of power, as explored through the manipulation of language, and sometimes poorly judged actions. There is almost no better exploration in scene of the shifting of power between two characters in all of literature, except perhaps the book scene in Ishiguro's Remains of the Day, or Richard Bausch's "Someone to Watch Over Me."

(Disclaimer: I am being deliberately vague in my not using any examples. To give examples would be to wrongfully mislead you into thinking a certain thing about either character, especially when so much hinges on the reader's interpretation of ambiguity.)

All of this leads to the ultimate display of power, or the only means by which a character/person who has been made to feel powerless can yield power again. A shocking ending, not in its occurrence as the dynamics of the characters builds to it, but in its ferocity. And a final line that places the entire motives of both characters into question.

As stated above, I do not regularly attend the theater, but I would make an exception for this.

I always read a Tom Robbins book with a box of salt, with the full knowledge that I will not be able to read another Tom Robbins book for at least a half dozen years. I can imagine it's the same feeling people have with sky-diving ("It was exhilarating! Such an adrenaline rush! I'm never doing it again") or like my father with a box of chocolate covered cherries. My father did not like chocolate and did not have a sweet tooth, but about once every five years or so he would buy a box of those confectionery treats at the movie theater and down the entire package before the opening credits had stopped rolling. This held him for four, five, six years.

The trouble with Tom Robbins (and no one ever refers to him by his surname alone) is that he is a linguistic pyrotechnician. He dances around a dictionary like Baryshnikov, does somersaults off a thesaurus, tumbles and twirls and flips and flounces in air heavy with the long pauses of people stammering for the right word; he plucks those words off the tips of their tongues and crumbles them in his hands before throwing nothing in the air like a word-crazed magician. His writing is the equivalent of one of the longest innovative fireworks displays. But just like those fireworks, impressive as they are, after the explosions and diaphanous colors igniting the night sky, what are we left with? A loud ringing in our ears and a lot of detritus and exploded paper on the ground that someone has to clean up. There's no substance, or some substance and metaphor and symbolism buried under a slowly dissipating smoke. We feel great while it's happening, but it doesn't usually last.

This collection is even more of a fireworks display than any of his novels. With the novels we are given a continuous story, a plot, a grounding so that when Tom goes off on one of his peyote-induced tangents, we know where we can always return. In this collection of short writings, there is no grounding, only Tom Robbins in all his excess and grandiosity.

It's fun, it's funny, it's intoxicating. But only in doses. Reading Tom Robbins is that moment you have when watching a Jack Black film and you begin to think how much fun it would be to hang out with him in real life; you begin to imagine that night, and you realize that no no no no no that would not be a good idea, and you are so happy there's a cathode-ray barrier between you and the frenetically self-absorbed comedian. Being forced to be feet, inches away from that hyperkinetic of a cosmic force would make you either flee in terror or punch Black in the face. Which is exactly how I feel about Tom Robbins. I love his work, his incontrovertible embrace of the absurd, his ability to weave such incongruous topics and references such as Dostoevesky, Camel cigarettes, obscenely large thumbs, and a canoe ride in Tanzania into one connecting quilt; I also sometimes want to kick him in the crotch.

Writers and readers wax poetic and obsessively about the love/hate relationship with David Foster Wallace, and it's a well-deserved ambivalence the unfortunately late writer has engendered. But Robbins should be mentioned just as often in the same context, and for the same reasons.

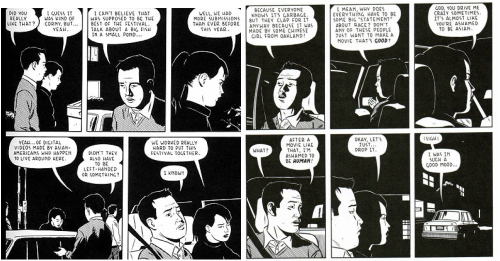

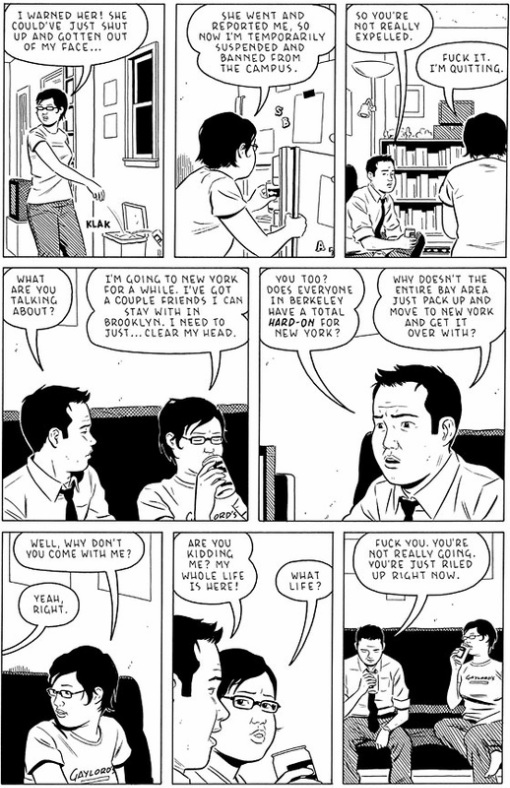

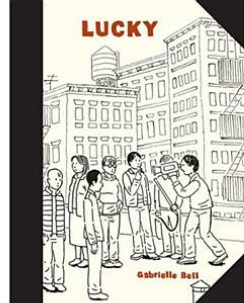

2011 is my year of the graphic novel. Early on I distinguished between comics and graphic novels. I wanted to read those stories that seemed to have more realistic and less fantastical, superhero based story lines. (That could be groundings for a future blog post or, hell, even a doctoral thesis: what distinguishes literary from genre fiction? Why isn't genre fiction considered literary, etc.) A friend recommended Gabrielle Bell and, after seeing my review of Lucky, asked if I had read his other recommendation: the Optic Nerve series. I told him the library did not have it, but they did have Tomine's Shortcomings. "You read Shortcomings?" Shortcomings, although his first full-length book, is not usually the first book used to introduce someone into Tomine. Something comparable would be recommending Finnegan's Wake to someone who has never read Joyce, or proposing to someone on the first date: it's generally not a good idea, you want to ease into things like that. Shortcomings is generally considered Tomine's masterpiece, at least until his next book comes out. It's ostensibly about Ben Tanaka, one of the most unlikable protagonists in recent memory. Ben is a dick. He's critical of everyone and everything; he picks fights with his long-time girlfriend Miko, he mocks the films in the festival she organized; and, like most flawed narcissists, he has a magnifying glass on everyone's faults but a blind spot towards his own.

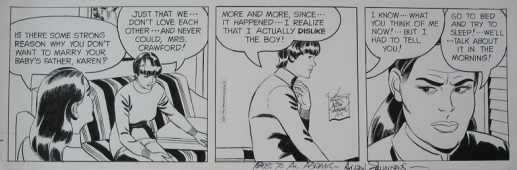

That said, he's also very smart, and very loyal to the few friends he has (especially Anna, with whom he has some of the best verbal sparring, primarily because she calls him on his caustic bullshit). He can be charming, as he woos two different girls later in the story. He's not violent and doesn't partake in illegal, dangerous activities. The disintegrating relationship between Ben and Miko is the catalyst Tomine uses to explore race and culture, and how societal and cultural expectations affect self-identity, if at all. As you can see, it's pretty light reading. At one point Miko accuses Ben of deliberately harboring hatred towards Asian culture, thereby implicating both Ben and Miko as objects of his ire. She points out that all the porn Ben owns is of white, blond women, an accusation that his fantasies do not include Asian women, and therefore he does not like Asian women. Ben denies this and in the next scene Ben is criticizing the technical quality of the DVD itself. However, the first two dates he goes on after Miko moves to New York to pursue film, are with white, blonde women, perhaps affirming Miko's accusation all along. Does this make Miko right? Does Ben have a type? Does Ben have issues with his own culture and what is expected of him? Why should Ben, as an Asian male, be expected to date Asian women? Should there be any self-inflicted expectations based on culture? To his credit, Tomine does not answer any of these questions, nor does he judge any of his characters. He doesn't show Ben in a needlessly negative light or as a misunderstood genius who's just too hurt inside to show his tenderness. Ben's a complicated, caustic human being. Tomine's graphic novels work like a stageplay. We don't know the internal motivations of the characters, or their background; we're just observers. I originally intended to write a negative review given the expectations I had after reading the dust jacket. It reads: By confusing their personal problems with political ones, Ben and Miko are strangely alone together and oddly alike... Being human, all too human, they fail to see that what unites them is their hypocrisies, their double standards. This gray zone between the personal and political is a minefield Tomine navigates boldly and nimbly. The charged, volatile dialogues that result are unlike anything in Tomine's previous work or, for that matter, comics in general. I saw the societal and cultural implications, and thought it raised great questions about culture and race and self-identity that are very rarely covered in literature, let alone comics. I thought it raised strong questions about sexuality and gender within that cultural landscape as well. I just didn't see the "political" implications. But I couldn't bring myself to write a negative review: it is insightful, provocative, well-written. The characters are three-dimensional, complex, sometimes unlikeable. The drawings fit the story, they possess a minimalist Mary Worth style. Compare below: I mentioned this to my friend, who, for the record, is Asian. Most of the people he had discussed the book with saw the political implications. He also said those same people were Asian. And so, in that moment, during our conversation about Shortcomings, the cultural insights and observations Tomine discusses were being acted out in the coffee shop, an unintentional meta-narrative-cum-commentary.

But that raised a different question for me. If I didn't catch everything that supposedly was explored in the book, did that make me a bad reader? Should we hold ourselves accountable to dust jackets? Obviously, no, on both accounts. We should not hold ourselves accountable to a dust jacket, and it doesn't make us bad readers if we "don't get it."

My issue came not with the book or with Tomine. It was with the dust jacket and my interpretation of the word "political". I think of "political" and I think of lawmakers, politicians, and the daily political theater of our Congresspeople. Perhaps naively (intransigently?) I think the word "politics" should be relegated to this arena, and not mixed in with what has become accepted lingo: cultural politics, sexual politics, office politics. Let's leave the word "politics" where it belongs: with the politicians.

I shouldn't hold the dust jacket or a single word against the book. Tomine didn't write the dust jacket. The publisher did. Tomine did write the contents inside the book, though. And this book, and Tomine's work I whole-heartedly recommend.

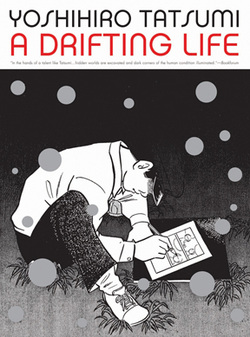

I wish I knew more about Tatsumi before I started reading the book. I took it out of the library due to a few factors: 1) 2011 is my Year of the Graphic Novel; 2) I had not seen a graphic novel with as epic a page count as this (855, including the appendix--I'm a notes reader), so I thought it would be an ambitious read; 3) the scope of the book seemed interesting for a graphic novel, and ambitious writers, even if they fail in their ambitions, always appeal to me, sometimes more than safe writers; 4) it was in the same area in the library as a few other books I had been looking for, so serendipity and random selection I suppose played its part; 5) it was published by Drawn and Quarterly, who I have quickly realized are almost flawless in their book selections. Drawn and Quarterly is the graphic novel equivalent of Matador or 4AD Records: if you like one or two releases from this label/publication, chances are you will like almost everything they produce. The book chronicles Tatsumi's (or Katsumi's, as he calls himself in the book) life starting from when he began writing four-panel comic strips as an early teen, to the point when he became a major force in the Japanese manga marketplace, and his gekiga became an accepted form. The fact that I knew so little about this author, the history of manga, and his notable place in the history and evolution of manga appealed to my omnivorous sensibilities: I am naturally drawn to the unfamiliar. If someone is not too daunted by an 800+ page book, I highly recommend it. And since it is a graphic novel, that 800+ page count (and subsequent reading time) can be significantly reduced. However, I cannot give this bildungsroman 5 stars, though this is primarily based upon my own Western reading conventions and prejudices. There are many times where Tatsumi introduces information or a character, and tells us in an aside in the panel itself what is to happen with that character. For instance, in the beginning of the story, a young Katsumi is asked by his father, a delivery man, to make his deliveries for him to a couple of women. Katsumi does, and the women read the letters attached to the delivery. An aside in the panel says that Katsumi would not understand the role of these women in his father's life until much later. But the author then drops that thread. We never return to it, and are never told anything about those women, or what the significance of the letters to them were. There is also a small plot thread involving a young female classmate of Katsumi's sister, who accompanies her to school everyday. After a certain time the classmate comes to the house late repeatedly. It is inferred this is in order to have a 30-second interaction with Katsumi, who always answers the door. We are told in another panel aside that someone would try to play matchmaker between Katsumi and this girl four years later, but we are never shown the results of this romantic possibility. There are other instances where future information is given the reader but we never reach the point where this information is relevant. Katsumi also provides historical, societal, and cultural information to the reader throughout the book, like a pop-up information of what was happening in Japan at the time politically, societally, and culturally. Blocks of pages are reserved every so often to let us know what films were showing, what music was popular, how Japan was recovering from WWII and becoming an industrialized power: a veritable Japanese historical encyclopedia. Perhaps the biggest compliment I can give the book is that it makes me want to read more about Tatsumi, and to try to find some of his early manga/gegika stories, if only to fill in the blanks of the stories he began in A Drifting Life. Perhaps, much as I found the book while rummaging through library shelves in search of something else, other books, perhaps I will discover some of Tatsumi's early works in the same manner. goodreads review

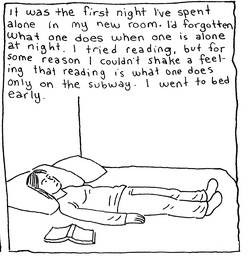

Continuing my 2011 fascination with graphic novels, I read Gabrielle Bell's Lucky yesterday. Much has been written about her minimal cartooning style, her insights and lack of romanticism about life as a twenty-something artist in NYC, which paradoxically makes her work (and her) charming. Much has been made of her capturing the spirit of an entire generation and lifestyle of people, while still living that particular lifestyle. I will not do any of these in this unorthodox review, for it has been stated in many reviews. Two quotes from the collection resonated with me the most, especially in light of my own transition to living in the city. They also reflected two of my biggest loves--reading and running--and how my relationship with them has changed while living in the city:"I tried reading, but for some reason I couldn't shake a feeling that reading is what one does only on the subway." "I decided to go jogging instead. I often go jogging when I feel like I have no control over anything." For insights like those, for cutting through the red tape of our brains much faster than any visit with a psychologist ever could, I'll choose Lucky.

One of the reviews on the back cover of First Love, Last Rites reads, "There's an assured and terribly macabre depravity about Ian McEwan's short stories..." I would have to agree with this statement. However, McEwan saves what could be a read about despicable people by coloring them with a sense of innocence, of curiosity. Most of their horrific deeds (including trying to have sex with one's younger sister, a husband and wife who make Taylor and Burton in Virginia Woolf seems like the Bradys, dressing your adolescent nephew as a girl and getting him drunk on wine, etc.) are not predetermined. Most of their actions are spontaneous, the characters' motives unknown to both the reader and the character. Even a story like "Butterflies," a first person chronicle of one of the worst crimes imaginable, is rendered mildly sympathetic, at least enough so that we don't turn away and shut the book, or move on to the next story.

These are not stories for the faint of heart. McEwan is tapped into the darker recesses of the human psyche, those parts we don't share with the world, or even admit to ourselves. But the writing is so crisp, vibrant, assured, that we will follow it anywhere.

The world is not all rivers of gumdrops and candy cane mountains, this we all know. Everyone has creeping thoughts that, for the most part, they don't act on. Thankfully we have Ian McEwan to show us what the people who do act on those thoughts are made of. And that these people are still human.

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed